|

|

|

Maureen Gupta Chapter of Doctoral Dissertation, Revised September 2008 Léon Bakst and the Décor of The Sleeping Princess Introduction In July of 1921 Serge Diaghilev engaged his long-time collaborator, the stage designer and artist Léon Bakst (1866-1924), (fig. 1, self-portrait) to produce the sets, backdrops and drop curtain, and costumes for The Sleeping Princess. [1] The Ballets Russes production was based on the Chaikovsky/Petipa ballet, The Sleeping Beauty, which premiered in St. Petersburg in 1890. Among the notable aspects of this new production – it was the first full-length Russian ballet presented in the West in the twentieth century, with principal roles danced by academy-trained Russian classical dancers [2] – is its unique place in the Ballets Russes repertory. Never before, and never after, did the Ballet Russes fill an entire evening with a late nineteenth-century Russian ballet. [3] Diaghilev had initiated his Saisons Russes in Paris in 1909 with operatic and balletic excerpts from larger works, as well as short one- or two-act ballets such as Le Pavillon d’Armide and CléopČtre which had been adapted from earlier productions in St. Petersburg. [4] As his cadre of dancers, choreographers, stage designers, and composers developed, Diaghilev would typically offer three short, newly or recently composed ballets in a program. Always desiring to astonish, this cavalcade in itself constituted a spectacle. For The Sleeping Princess Diaghilev and his collaborators endeavored to create a different kind of spectacle, one sustained by a single work over the course of an evening or matinée. As the London Daily Mail reviewer wrote after The Sleeping Princess’s premiere, “This new ballet…out-splendours splendour,” [5] and indeed that was one of the goals of Diaghilev and Bakst for this production. By 1921 the Ballets Russes had dazzled audiences for over a decade; Bakst and his brilliantly colored, exotic designs for CléopČtre, Shéhérazade, Le Dieu Bleu and others were in large measure responsible for the sensation created in Paris early on. In these short, modern works, Bakst’s aim was to capture the essence of a ballet. “From each setting,” he told art dealer and critic Martin Birnbaum in 1913, “I discard the entire range of nuances which do not amplify or intensify the hidden spirit of the fable.” [6] Bakst did indeed seek to capture the essence of Sleeping Beauty in his décor, but my analysis indicates that he moved beyond “intensify[ing] the hidden spirit of the fable” by casting The Sleeping Princess in a nostalgic, Symbolist-tinged rendering. His youthful admiration of the Chaikovsky/Petipa ballet, seen thirty years prior, was transformed through time and maturity into a vision that Bakst articulated throughout the ballet, with layers of allusions and illusions. 1 |

|

Fig. 1 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Insisting that the program include the phrase, “The entire production by M. Leon Bakst,” the designer undertook a complex set of décor requirements – all to be completed in about three months, from early August to early November 1921. The Sleeping Princess required five scenes [7] in two different time periods and approximately 270 costumes. These consisted of costumes for thirteen principals (and two costumes each for the Queen and King, Aurora, Cantalabutte [sometimes spelled Catalabutte], and Prince Charming, as he was named in the English program); over twenty costumes for the fairy tale divertissements in Scene V; costumes for the four foreign princes; and numerous other costumes for ministers, lords- and ladies-in-waiting, nurses, village maidens and youths, dukes and duchesses, marquises and marchionesses, beaters and huntsmen, baronesses, and nymphs; mazurka ladies and men; and lackeys, footmen, guards, and pages. Bakst rose to this daunting task and created the décor of the ballet through an extraordinary array of costumes and scenography, drawing some of the designs from earlier efforts. But significantly, Bakst envisioned his role in The Sleeping Princess as more than a supplier of designs for sets and costumes. The designer sought to create the mise-en-scŹne in numerous ways. In the large crowd scenes he paid attention to the effect created by careful massing of bodies and their colors. He altered the entry of the opening processional to enhance movement and direct the gaze of the audience. Throughout the backdrops for the five scenes, Bakst’s artistic vision changed from an emphasis on line to an emphasis on color, and finished with a linear backdrop. The backdrop for Scene I, the Christening, was architectural and formal and delineated the public christening and ceremonial giving of gifts to the baby Aurora. For Scene II, the Spell, Bakst created a softer milieu, a colonnaded garden in which Aurora receives her courtiers and pricks her finger on the spindle. Scenes III and IV, the Vision and the Awakening, were yet more atmospheric and intimate in Bakst’s depiction of a deep forest at twilight where the Lilac Fairy shows Prince Charming a vision of Aurora, and of Aurora’s rose-colored bedroom softened with curtains and bathed in moonlight. In Scene V Bakst returned to a linear scenography for another public ritual, the Wedding. Though there is no archival evidence specifying who chose the fairies’ new names, Bakst and/or his collaborators changed some of the fairies’ original names to those explicitly evoking aromas: Pine Woods, Cherry Blossom, and Carnation replaced Candide, Coulante or Fleur-de-Farine, and Miettes-qui-Tombe. The Fairy of the Mountain Ash (or Larch) was added and danced to the Fairy Lilac’s Variation in the No. 3 Pas de Six. The Fairy Humming Bird, or Colibri, replaced Violente (sometimes spelled Violante). The humming bird evoked flowers, nectar, and pollination, and Violente’s choreographic finger-pointing and brisk footwork could with little adaptation suggest the speed and darting motion of a humming bird. The Fairies Lilac and Canari-qui-chante (called Fairy of the Song-birds) remained the same.

2 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

With his work in The Sleeping Princess, Bakst returned to the kind of over-arching role he had envisioned for himself when he wrote to art critic Huntley Carter around 1911 (fig. 2):

Continue to the NEXT PAGE

3 |

|

Fig. 2 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

In part this statement reflects Bakst’s efforts to promote his expertise; it also reflects his contempt toward “the bad taste absurdities of learned directors,” or those referred to as “snob aesthetes” at the time. But what Bakst wrote above probably reflects the reality of his experiences with the Ballets Russes, which in the early years were intensely collaborative efforts of Diaghilev and his Mir iskusstva colleagues. Bakst was deeply involved in developing the libretti for a number of early ballets. [9] As the decade progressed, Bakst became increasingly marginalized from new Ballets Russes productions, and Diaghilev favored French easel painters such as Picasso, Matisse, and André Derain. Bakst’s engagement for The Sleeping Princess represented a chance (his final chance, as it turned out) to create the “absolute unity guided by a scenic mind” in such a large-scale work. 4 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

The challenge with The Sleeping Princess was not only that it was a massive ballet to produce, but also that it had been done before. Bakst’s approach to this ballet contrasted with prior Russian productions of full-length ballets in which different artists designed discrete pieces of scenery and costumes. Vladimir Telyakovsky, Director of the Imperial Theatres from 1901-17, recounted the practice with regard to décor of nineteenth century ballets at the Imperial Theatres, “Designers were divided according to their painting specialties: architectural, forest, marine, and other types of décor. These designers never did costume or prop design….When a new production was staged, the décors of the acts, painted by various designers, were assembled, as well as the costumes and props, executed according to the designs of Ponomarev, Vsevolozhsky himself [Telyakovsky’s predecessor], and others. The manner of execution, the tones, and colors – all of this differed in each act, often they didn’t suit each other at all, and it was impossible to gain a coherent impression from the entire production.” [10] In a 1910 interview, Diaghilev and Bakst expressed what was different about the Ballets Russes approach to scenography. “The French were the first to be astonished to learn from us that scenery does not have to represent an exterior or an interior but has to create the atmosphere, the artistic framework for the play,” said Diaghilev. Bakst continued, “I’ll tell you what the secret of the Russian ballet and its success is. The secret of our ballet lies in its rhythm. We have learned to convey, not feelings and passions as in the drama, nor form as in painting, but the very rhythm of feeling and form. Our dances and scenery and costumes – everything grips because it reflects the fleeting and secret rhythm of life. Our ballet appears as the synthesis of all the existing arts.” [11] In The Sleeping Princess, Bakst created rhythm by juxtaposing the large scale with the intimate, and neoclassical architectural spaces with romantic dreamscapes. He contrasted the painted illusion of space with a room actually constructed of stage properties. By manipulating the set and massed costume colors, and through his changing emphasis on line and then color, Bakst created a rhythmic flow that governed the scenic progression of events. This rhythm expressed the essence of The Sleeping Princess: the sense of flux that lies at the heart of the story and the music; the tug between good and evil, the fairy world and the terrestrial realm; and the disrupted order and authority in Florestan’s realm and its restoration. Bakst used visual imagery to guide the audience’s perceptions of the choreography and the music. As articulated in the letter to Carter, Bakst believed that “the ‘decor’ cannot have elements of form and colour… other than those specially chosen by a single scenic mind which unites everything in perfect harmony.” Through his control of the visual focus of the ballet, Bakst differentiated the formal, public moments that begin and end the ballet from its private and, in Bakst’s imagining, erotic core. It was through his décor that he consciously counteracted the essentially static nature of the ballet in which the entire story is foretold in the beginning, by imbuing the production with what he called “the very rhythm of feeling and form.” [12] 5 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bakst’s intensely personal imprint was itself a reflection of his Russian Symbolist aesthetic. W. A. Propert noted the impression of Bakst’s individual style: “The production [of The Sleeping Princess] was in its way quite superb, and the ensemble worth of a Gala night in St. Petersburg….As for the decoration, one can safely say that nothing like it had been seen in our time, not only in its extent and disregard of cost, but above all in its endless invention and its sustained level of admirable taste…. these elements had been blended into so masterly a whole and sharpened with so personal a fantasy that the completed design was pure Bakst, and Bakst of the finest kind.” [13] Bakst’s concern with capturing what he saw as the essence of a work such as The Sleeping Princess, and his very personal interpretation, can be attributed to his aesthetic development in St. Petersburg during the heyday of the Russian Symbolist movement. In 1890, at the age of twenty-four, he experienced the premiere of The Sleeping Beauty at the Mariinsky Theatre. He met Diaghilev, Benois, and others and joined their private discussion group called the Nevsky Pickwickians. These friends along with others later formed the heart of the World of Art group, and its journal, Mir iskusstva, published from 1898-1904. [14] In the third part of his introductory essay “Complicated Questions” for the new journal, titled “In Search of Beauty” (1899), Diaghilev wrote of the relation between the artist’s imagination and his work: “Fantasy has to be clothed in flesh; only then will it be visible and understandable to others…. No one dares to insult the mystery involved in the relationship of the creator to his dream, but he must lead us into his kingdom and show us, clearly and in real terms, the images that without his help are hidden from us.” [15] In the fourth part of the essay, “Principles of Art Criticism” (1899), Diaghilev proposed that “we do not agree that a work of art is a piece of nature observed through temperament,” alluding to Emile Zola’s definition of art as “un coin de la création vu ą travers un temperament [a piece of nature seen through a temperament].” Diaghilev preferred to invert the phrase. “Beauty in art is temperament expressed in images,” he continued, “and therefore it is not important in itself except as an expression of the personality of its creator….The highest expression of personality, irrespective of the form it takes, is beauty created by man. The artist is the all-embracing source of the innumerable artistic moments that we have experienced. Why, then, should we seek an explanation apart from him? It is surely a matter of indifference to us where he draws the inspiration for his work or in what outer form his thought takes shape.” [16] That Bakst’s mature work in The Sleeping Princess was so clearly described in these early expressions of Diaghilev and the World of Art group indicates the continuing effect of these early experiences on Bakst’s aesthetic principles. Like other Russian artists during this time, Bakst explored color and synesthesia. Rimsky-Korsakov and Scriabin attempted to evoke different colors through their orchestration, and some Russian Symbolist poets chose words to emulate musical sounds; Bakst infused some of his décors with “visual” aromas. [17] In The Sleeping Princess, the attributes of the fairies emulate the smells – and sounds – of spring. The interpolation of the Arabian (coffee) and Chinese (tea) variations from The Nutcracker into the Scene V divertissements also added aroma. Bakst accentuated or included other important themes from Russian Symbolism in his décor. One of these was a heightened awareness of boundaries between worlds, twilight and transformation, evidenced in Bakst’s treatment of the Vision and the Awakening scenes with their emphasis on mood and saturated color. Bakst’s adaptation of baroque scenographic models and court ballet costumes was an aspect of retrospectivism, another important Symbolist concern. The influence of Russian Symbolist debates regarding Apollonian versus Dionysian aesthetics in poetry, philosophy, and art can be seen in Bakst’s contrasts between the austerity of line versus the intense emotions represented by color. There are other ways that Bakst’s treatment of the décor reflects Russian Symbolist aesthetics: his reference to St. Petersburg’s Bronze Horseman in the Vision scene and the poetic themes it evokes; and the sexual imagery in the Awakening that recalls poet Aleksandr Blok’s cult of the Beautiful Lady. 6 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

For Bakst, the opportunity to create the décor for The Sleeping Princess meant revisiting his own past, the imperial St. Petersburg of thirty years prior, when he had been a struggling artist yet to receive a stage commission. As the 1890 Chaikovsky/Petipa production of The Sleeping Beauty was itself retrospectivist, using the court of the Sun King as a metaphor for Russian monarchy and Aurora as the dawn of the Russian ballerina, [18] so too was Bakst’s Symbolist conception retrospectivist. He recalled the city of his youth from which he had been cut off, having been expelled from St. Petersburg in 1912 for being Jewish. [19] Further, the Revolution of 1917 swept away the world in which The Sleeping Beauty had been conceived. Bakst’s décor, with its many allusions to Russian Symbolism, was a profound comment on what had disappeared, as well as on the very process of disappearing. As the philosopher and theologian Vasilii Rozanov wrote, “The essence [of Symbolism] is precisely…in the discovery of things invisible, or rather and still better: in the covering, the ‘vesting’ of things invisible. Everything is ‘vested’ in robes and history itself is the enrobement of invisible, divine plans.” [20] Rozanov’s definition of Symbolism is particularly ą propos because for Bakst, his costumes for The Sleeping Princess were a literal vesting of bodies, many of them representing symbols – of youth and dawn, of monarchy, of fairy attributes – and his historicizing was both retrospectivist and nostalgic. By 1921 avant-garde artists in Europe were exploring dadaism, expressionism, and constructivism. Bakst was ill at ease with those trends. But given free reign in a ballet he understood, he guided all aspects of the décor of The Sleeping Princess with a sure hand. It was the culmination of his artistic career, yet at the time it was deemed a meaningless spectacle. [21] It was Bakst’s misfortune to present a revival of a major work of art expressed in a Symbolist sensibility, at a time in which that sensibility had passed. 7 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bakst’s Program Essay, “Tchaikovsky at the Russian Ballet” The extensive essay Bakst contributed to The Sleeping Princess souvenir program, “Tchaikovsky at the Russian Ballet,” set the stage, as it were, for the designer’s interpretation of the ballet. The essay touched on predominant elements of Bakst’s production: the play of colors amidst a setting of splendor, a nostalgic memory to his own attendance the 1890 dress rehearsal in St. Petersburg, his retrospective use of Baroque and French models of décor, and enchantment with a dream world. He began his essay with a remembrance of The Sleeping Beauty:

8 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bakst placed his evocation of Russian Imperial grandeur in the program to impress his audience and prepare them for the spectacle about to unfold. His description may also have been meant to appeal to Londoners’ nostalgic memories of the Coronation Gala at Covent Garden (June 26, 1911), in which Diaghilev’s troupe performed part of Le Pavillon d’Armide. The prewar extravaganza featured an assemblage of royalty (including the King and Queen of England and the Aga Khan), jewels (Queen Mary wore the Cullinan diamond and the Star of Africa), Peers, Orders, and all in a theatre festooned with thousands of roses and orchids. [23]Also, Bakst’s recollection of the Mariinsky audience mirrored his own conception of Scene I, based on the colors gold, red, and blue. A prominent blue velvet canopy over the baby Aurora’s crib and the blue cloaks of the King and Queen with long trains accent the gilt of Bakst’s backdrop. Royal blue, pale sky-blue, and peacock blue were the prominent colors of many of the costumes of royal attendants, such as the Queen’s Pages, the Lackeys, and the King’s Herald. Bakst replicated the “red coats and white stockings of the court” in the painted guards standing at attention in distant staircases, as well as in the onstage costumes for the Negro Footmen. Noted The Dancing Times, “When…all was prepared for the entrance of the fairies, it was found that on the left of the stage facing the royalties were the bright red and scarlet costumes, while on the king’s side all was blue and white.” [24] Bakst’s mention of imperial eagles in his program note was significant. One of the important symbols that Bakst intended to include in the ballet was the massive, three-dimensional eagle perched above Aurora’s bed during the Awakening scene. In his program essay Bakst conjured a Symbolist haze around his nostalgic memory, and he linked Chaikovsky’s music to the “Slav soul.” Bakst portrayed his heady intoxication with The Sleeping Beauty in sensual terms of color, light, sound, and aroma. He deliberately contrasted the dazzling with the murky, a world of dreams with harsh reality, and the commonplace with the noble. These were frequent subjects of Russian Symbolist poets and novelists during the fin-de-siŹcle, though not explicitly part of Petipa’s libretto. [25] The tone of Bakst’s impressions of The Sleeping Beauty bears a close resemblance to this excerpt from Baudelaire’s Richard Wagner and Tannhäuser in Paris (1861).

Like Baudelaire, Bakst described being transfixed by the “radiant flow of refreshing and beautiful melodies, which were already friends,” and he “lived in a magic dream” of intoxication. The inspiration for Bakst was the music of Chaikovsky rather than that of Wagner. [27] “In Tchaikovsky…this ‘Muse,’ is…very human, sensitive and high-strung, sometimes in tears, and also madly dancing – in short, the Slav soul, is it not?.... it is a joy, and a delight, to build up in our clan, hardened as it is by continual conflicts, this homage to the great musician who succeeded so well in reflecting the Russian soul.” And in the closing paragraph of his essay Bakst asserts that the genius of Chaikovsky’s music and the splendor of the Russian monarchy inspired his décor: “Well, for me, a painter, true greatness is revealed in this ballet of ‘The Sleeping Beauty.’ The musician has had no recourse to pasticcio, which might seem obligatory in treating the period of Louis XIV. No. Tchaikovsky remains here, as elsewhere, Russian in spite of all. But, through the absolutism of Alexander III, with its pomp and splendour, Tchaikovsky’s genius impels our thoughts to the broad decorative lines of the seventeenth century and the magnificence of the Roi-Soleil.” [28] Here, Bakst hints at his borrowings from the Bibienas as well as other decorative motifs from the Sun King. Yet in his essay he also shows his aesthetic disdain for those who slavishly follow the latest trends, like the “futuro-cubist, always hailing from the ranks of unsuccessful engineers.” In many ways Bakst’s décor for The Sleeping Princess was both a rapprochement with his Russian past and a re-assertion of his aesthetic principles, which were founded in the Russian Symbolist movement. 9 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bakst and the Russian Symbolist Movement Bakst’s exposure, as a spectator, to The Sleeping Beauty came near the beginning of his artistic career, and his contribution as an artist for The Sleeping Princess came near its end. In between were his formative experiences primarily in Russia with the Nevsky Pickwickians, Diaghilev and the World of Art group, and his prominence attained subsequently with the Ballets Russes in the West from 1909 forward. Prior to the Ballets Russes, Bakst participated in the many aesthetic debates among those artists, primarily writers, who constituted the first and second wave of Russian Symbolists. [29] Writing toward the end of Symbolism as a movement in Russia, the poet Andrei Bely (pseudonym of Boris N. Bugaev, 1880-1934) identified the prime outside sources that had influenced Russian Symbolists: “Two patriarchs of the ‘symbolist movement’ engraved with their whole life and work the postulates (lozungi) of the new art in the literature of the second half of the nineteenth century; these patriarchs are Baudelaire and Nietzsche.” [30] Many of the important themes of those two writers were assimilated and re-interpreted into the essays, lectures, and writings of Russian aesthetes. Bakst’s approach to The Sleeping Beauty reflects a number of these themes, which included correspondences between realms of consciousness, attention to the synesthetic attributes of color, and the Apollo/Dionysus dichotomy. The retrospectivist aspect of Bakst’s décor was also an important part of Russian Symbolist movement. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, the young Russian writers and artists who had come to be known as “decadents” were fascinated by the poetry of the French and Belgian Symbolists, Baudelaire in particular. [31] Bakst’s first serious study of this poetry may have taken place during his participation in the Nevsky Pickwickian group.

Although the official censor prohibited the publication of Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, individual poems from that volume had been translated into Russian since the 1860s (perhaps Benois was not aware of this). Bakst and the others were fluent in French and thus would have read any poetry and journals Birlé sent their way in the original language. But translations played an important role in the re-interpretation of Baudelaire’s poetry, as Wanner shows through comparative analysis, according to the aesthetic goals of the translator. Dmitri Merezhkovsky (1865-1941), a founding Symbolist writer who with his wife Zinaida Gippius (1869-1945) was later involved with Mir iskusstva, translated and published several of Baudelaire’s prose and verse poems in the 1880s. By the mid 1890s Valerii Briusov (1873-1924) published three compendia containing his own poems interspersed with new translations of poetry by French and Belgian Symbolists. 10 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

In tandem with Russian encounter with French Symbolist poetry was an upsurge of interest in the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche. Discussions of his work, in the form of lectures and publications, began in the year of Sleeping Beauty’s premiere, and continued through 1909-10 when Bakst began working steadily in the West. Pyman notes two sources generating interest in Nietzsche in 1890: “[Nikolai] Minsky is often credited with the introduction of Nietzschean ideas to Russia on the strength of ‘Starinnyi spor’ [his philosophical tract, By the Light of Conscience, 1890] but this is not how his contemporaries saw it. Hippius says it was Prince Urusov who concentrated the attention of the literary elite on the ideas of the German philosopher in a talk given in 1890 when, according to Viacheslav Ivanov, ‘everyone was beginning to discuss Nietzsche.’ ” [33] One aspect of Nietzschean philosophy that resonated with artists and writers was the fin-de-siŹcle feeling of an era coming to a close; this merged with the feeling of some Russian Symbolist decadents of the kind of decay and putrefaction expressed in many of the Fleurs du Mal poems. In 1892 Merezhkovsky gave a lecture titled “The Reasons for the Decline and the New Currents in Contemporary Russian Literature” in both St. Petersburg and Moscow published a book of essays under the same title a year later. This sentiment was expressed famously in a 1905 speech by Diaghilev at a banquet given in his honor: “I can say boldly and with conviction that whosoever is certain that we are witnessing a great historical moment of reckoning and ending in the name of a new, unknown culture is not mistaken – a culture that has arisen through us, but will sweep us aside. And hence, with neither fear nor doubt, I raise my glass to the ruined walls of the beautiful palaces, as I do to the new behests of the new aesthetics.” [34] Another aspect of Nietzschean philosophy was analyzed in 1896 by the writer Akim Volynsky (1863-1926) in his article titled “Apollo and Dionysus” in Severnyi Vestnik (Northern Herald). [35] Others took up the idea of such a duality. In 1902 the Symbolist poet Viacheslav Ivanov (1866-1949) published a volume of poetry, Guiding Stars, in which the poetry was divided into cycles. One entire cycle concerned the theme of Dionysus. Many of the Symbolist debates took place in Mir iskusstva (1898-1904), as well as in the other journals and publishing houses active in Moscow and Petersburg during this time and Bakst was actively engaged in these activities. [36] The artist, who had studied with the Finnish painter Alfred Edelfelt (1854-1905) in Paris from 1893-96, returned to St. Petersburg as Diaghilev began organizing his art exhibitions at the Stieglitz Museum (in St. Petersburg) and contemplating the journal which would become Mir iskusstva. [37] In Mir iskusstva, as in other journals and compendia, the fine arts were often considered in conjunction with the literary arts. The following demonstrates how artists and writers collaborated in one Mir iskusstva issue: “For Vol. V, No. 4 [April, 1901], [Diaghilev] planned a novelty – a set of poems with illustrations, which would tax the fantasy and graphic powers of his collaborators to the utmost. Ten pages of poems by Merejkovsky would be adorned by Lancerey and Bilibine; four pages of Sologub’s poems would be decorated by Benois; drawings by Lancerey and Bakst would illustrate respectively the verses of Hippius and Balmont; while Minsky would be interpreted by Lancerey.” [38] 11 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Fig. 3 Fig. 4 |

|

Mir iskusstva paid attention to both the Muscovite school of Neonationalists and the St. Petersburg group of graphic artists, who were also editors and illustrators of the journal. [39] As Acocella writes, “the Neonationalists were oil painters, while the St. Petersburg group favored pen-and-ink, watercolor, and gouache…. These preferences say a great deal about the style and tone of the two schools. Oil was consistent with the artistic temperament of the Muscovites: their vigorous experimentalism, their “peasant” vitality, their connection with the hopeful and visionary aspect of Symbolism. And the graphic arts were consistent with the Petersburgers’ refinement, their nostalgia, their alliance with the disappointed, fin-de-siŹcle wing of Symbolism.” [40] Bakst, the future colorist, labored in the black and white milieux of graphic design, layout, and photographic retouching for Mir iskusstva and the Yearbook of the Imperial Theatres (1899-1900) edited by Diaghilev. One of Bakst’s more important designs from that period was the colophon of the journal, an eagle atop a snowy mountain signifying the lofty nature of art, which appeared in 1898-99. This symbol, altered, would appear later in Sleeping Princess. In their work on Mir iskusstva and the Yearbook of the Imperial Theatres, Bakst and Diaghilev established early on in their collaborative relationship a commitment to quality, no matter the expense. Mir iskusstva was costly to produce and Diaghilev did not stint with illustrations and reproductions done on high quality art paper interleaved with heavy cream paper. Some engraving was sent out to Germany because the technology was not available in Russia. Bakst himself spent many hours obsessively retouching the backgrounds of photographs until the desired effect was achieved. Under Diaghilev’s aegis the Yearbook for 1899-1900 became a lavish work elevated far above its usual humdrum level. The edition impressed St. Petersburg and reportedly even the Emperor, but it ran 10,000 rubles over its budget of 20,000 rubles and Diaghilev was not asked to manage the next year’s annual. [41] Bakst’s taste for an unusual use of rich colors began to emerge with his involvement in theatrical design, which began a few years before the close of Mir iskusstva. Three of his first theatrical commissions were for the Alexandrinsky Theatre’s productions of Hippolytus, Oedipus at Colonnus and Antigone in 1902 and 1903. Merezhkovsky translated from the ancient Greek; the new translations reflected the Symbolist fascination with classical Greek culture. [42] As André Levinson pointed out in his 1923 biography of Bakst, in the production of Hippolytus “the young stage director, Osarovsky, hoped to make a grand coup. The play was translated by Merejkovsky in exceedingly beautiful verse and with an extremely intense modern feeling. Among the Russian intellectuals of that time, Nietzschean ideas were held in great fascination. Now, in this early masterpiece the philosopher had transfigured the whole conception of the spirit of the ancients. Under the marble-like and placid guise of the Greece of Apollo’s time he had revealed the Dionysiac ecstacy, the pathetic distress and the mystic impulse of the masses.” Levinson commented further on Bakst’s strong colors, especially in Oedipus at Colonnus: “The garments were brightcolored; the purple robe of Creon was resplendent with its ornamentation copied from Ionian pottery.” [43] In 1906 Bakst designed a new curtain for the Vera Komisarzhevsky Theatre, which had been opened by the actress in 1904; Bakst’s curtain was a view of Elysium influenced by his 1905 trip to Greece with his friend and fellow painter Valentin Serov. [44] Opening the 1906 season at the Komisarzhevsky Theatre, Vsevolod Meyerhold directed a Symbolist version of Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler. The décor, by Bakst, was completely white and chosen so as to set off the characters, each of whom was symbolized by a color. The fascination of many Symbolists with ancient Greek culture sharpened a debate in which the Apollo/Dionysus construct became a way of framing questions and examining issues regarding the nature of literature and fine art. The polemics peaked around 1909-10 as aesthetes advocated one approach over the other; Bakst’s writings and oeuvre from that time show how important these issues were to him. In the Symbolist journal Apollon, begun in 1909 after the demise of Vesy, a new group of prose writers and poets used architectural metaphors to prescribe the goals of a clear line, perspective, and proportion in place of mysticism and vagueness. In his essay, “On Beautiful Clarity: Notes on Prose,” Mikhail Kuzmin (1872-1936) advocated precision, logic, and consistency of genre in what he termed Clarism. The ideas of this influential article were later incorporated into the Acmeist movement of poetry. Bakst and Benois both contributed articles addressing art. Benois’s essay, in the inaugural issue of Apollon, was “In Expectation of a Hymn to Apollo.” Bakst’s lengthy essay in the second and third issues of Apollon was titled “The Paths of Classicism in Art”; it was reprinted as “Les Formes Nouvelles du Classicisme dans l’Art” a year later in La Grande Revue. In his essay Bakst advocated a return to child-like simplicity and “un style lapidaire,” based on the ancient Greek notion of physical beauty. “Les éléments de la peinture récente étaient l’air, le soleil et le feuillage; ceux de la peinture future sont l’homme et la pierre,” he wrote. [45] In contrast with the stiff, mannered style of Bakst’s essay propounding Apollonian restraint and simplicity is this 1909 description by Benois of his friend’s Dionysian infatuation with Greek art: “Bakst is completely taken with Greece; one must really hear the infectious enthusiasm with which he speaks of it…and one must see him at the Antiquities Departments of the Hermitage and the Louvre, pedantically copying the ornamental designs and the details of the costumes and the furnishings, to realize that what we have here is more than a superficial historical craze. Bakst is obsessed with ancient Greece, he is delirious about it and that is the only thing he can think of.” [46] Bakst’s art spoke louder than his pronouncements on the page, and his predictions regarding the future of painting did not come to pass. In his theatre work Bakst veered toward the Dionysian. This is seen in his first triumphs for Diaghilev’s Saisons Russes, the Orientalist décors seen in CléopČtre (1909) and Schéhérazade (1910) with their orgies of color, pattern, and sexual suggestion. As he admitted to his fellow artist and one-time pupil Anna Ostroumova-Lebedeva in St. Petersburg, “I myself am head over ears in colours, and don’t want to hear a word of black and white; I plan, on my return [from Paris], to convert both Kostia and Shura [Somov and Benois] to the “painterly” faith, and you too, of course, my dear Anna Petrovna. I have noticed that it is easier to sense and synthesize form through the medium of colour, which makes it more authentic and real.” [47] Bakst’s use of the term “painterly” was an allusion to the Muscovite style that emphasized color and mood. In contrast was the style of St. Petersburg artists that emphasized clarity of line and often featured architectural subjects. Benois, for example, was known for his articles and paintings devoted to St. Petersburg architecture, and had for some years extolled the neoclassical architecture of the capital city and its derivation from European models. Though Bakst was through proximity part of the Petersburg group of artists and writers, his own predilection for color placed him on the Dionysian side. Through his experience working with Diaghilev in Paris, Bakst realized that he could “synthesize form through the medium of colour,” that is, create large-scale forms in a backdrop by substituting masses of color for large linear shapes. This is apparent in comparing his scenography for CléopČtre (1909) with that of Schéhérazade (1910). In the earlier ballet Bakst used perspective and scale to establish the illusion of space. (fig. 3) The massive pink statues on either side (probably side cloths) lead the eye toward rows of low, heavy columns that open onto the Nile. The sky at dusk was a heavy purple. In Schéhérazade (see fig. 4) Bakst created theatrical space by juxtaposing saturated oranges, blues, and greens that contrasted and vibrated. Bakst’s richly patterned costumes then became in a sense moving parts of the scenery. As Bakst wrote to Diaghilev in 1911, “the whole essence of my designing for the theater is based on the most calculated arrangement of patches of color against the background of a set with costumes which correspond directly to the physique of the dancers.” [48] Art historian Huntley Carter gives the following description of Bakst’s décors:

12 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

André Levinson described Bakst’s décor for Schéhérazade as evoking a “vision filled with potent and mysterious charms…. the ethereal aroma of perfumes from a gripping fairy tale secret, and the color language of a completely different order.” [50] Benois mentioned that “Spicy, sensuous aromas seem to be wafted from the stage, but the soul is filled with foreboding.…It is difficult to imagine an exposition of drama more…to the point than Bakst’s décor.” [51] Bakst himself spoke his association of colors with particular emotions:

In 1910 Bakst was embarking on a new journey as theatrical designer for the Ballet Russes, while he was simultaneously in the process of disengaging from the world of Russian art. Yet what he carried with him were his formative experiences in the milieu of Russian Symbolism. Bakst never described explicitly his own aesthetic as Symbolist, and neither did any of his reviewers or critics in the West. His early efforts for the Ballets Russes showed his concern for color and its ability to stimulate other senses such as aroma and emotion or mood. In 1909-10 we note the seeming contradiction of Bakst’s invocation of Apollonian, classical principles with the praxis of his Dionysian décors, the kind of contradiction acknowledged by some writers as representing two sides of a coin rather than mutual exclusivity. As the Symbolist Viascheslav Ivanov wrote in 1910 in Apollon, in “This same dualism of day and night….both worlds…are together in poetry. Now we call them Apollo and Dionysus, we know their infusibility and inseparability, and we sense in every true creation of art their effective dual unity.” [53] Like many of the Symbolist poets around him, Bakst was living his art. 13 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bakst and the Rothschild Panels (1913-1922) Prior to The Sleeping Princess, there were two occasions where Bakst had considered the fairy tale The Sleeping Beauty. The first was a set of mural panels commissioned for the London residence of James de Rothschild. This commission was scarcely begun before the interruption of WWI, and was not completed until after The Sleeping Princess had premiered. The other project involved the designs for Anna Pavlova’s production of her own truncated version of The Sleeping Beauty in New York, in 1916, and is treated separately below. Because the Rothschild commission overlapped with Bakst’s theatre work for Pavlova and Diaghilev on the same subject, the paintings yield important insight into Bakst’s thinking with regard to the fairy tale.[54] Bakst received this unexpected commission of mural work partly as a result of his 1913 exhibition at the London Fine Art Society. Rothschild’s interests lay with golf and horse racing and he himself knew nothing of art, but he had purchased a townhouse in London and wanted custom panels for his drawing room. A friend directed his attention to the exhibition that had coincided with the Ballets Russes’ season in London. When invited to choose a theme for the murals, Bakst suggested The Sleeping Beauty fairy tale. Appropriate to a residential setting, Bakst conceived the seven Rothschild panels in a painterly rather than theatrical style. The themes of each panel were: the curse of the Bad Fairy, the spell of the Good Fairy, the Princess pricks her finger, the King pleads with the Good Fairy to save his daughter, the court sleeps for a hundred years, the Prince spies the castle while hunting, and the Princess is awakened with a kiss. [55] In Bakst’s allegorical depiction, important elements of the story were articulated through plane perspective and variety in painterly focus. It is quite likely that Bakst sketched the sequence and physical layout of the seven panels at the beginning of the commission, though dated sketches are not extant. Fig. 5 shows an example of one undated preliminary sketch, of the moment when the Princess pricks her finger. The reasons delaying Bakst’s completion of the commission were myriad: illness (Bakst spent most of 1915 convalescing in Switzerland from depression; Rothschild fought in the war and later lost an eye), the disruptions of the war, Bakst’s other commissions (including the one for Pavlova), and changes in decorators and houses. In a letter from 1917 to Edmond de Rothschild’s homme d’affaires, Gaston Wormser, Bakst reported on the delays he encountered producing the panels:

14 |

|

Fig. 5 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Fig.6 Fig.7 Fig.8 Fig.9 Fig.10 Fig.11 Fig.12 Fig.13 Fig.14 Fig.15 |

|

It was planned, at the request of the client, to insert portraits of Rothschild family members and their friends, as well as their pet papillon (and Bakst painted himself into the first panel). Due to the unavailability of the actual models during wartime, Bakst in frustration sketched and painted the scenes first and left the faces to be filled in later. A number of faces and nude studies from 1918 were used in the panels (fig.6) and (fig.7). There were other faces sketched in 1921 (fig.8) and (fig.9). Bakst returned to Paris just before the opening of The Sleeping Princess in November of 1921, and it appears that he completed much of the actual painting then. The dates of the intermediate stages of the panels are unknown. Three of the seven panels were dated 1922 and thus completed after the The Sleeping Princess ballet; the other four were undated. However, as a set the panels were not fully executed until 1922, and because of various delays and a cessation of correspondence it is not clear exactly when they were shipped and finally installed. It may have been 1923 or as late as 1924. Bakst referred to the work as “my ill-fated panels for M. de Rothschild.” [57] The panels in themselves reveal in microcosm Bakst’s mastery of tone, color and pattern, and point of view – elements that were also integral to his theatrical designs. The elaborate flowing gowns of the Queen and the Nurse in the lower third of the first panel, the baptism (1922), lead the eye toward a tiny crib holding the infant Princess. (fig. 10) Behind, reduced in perspective, stand the King and the “Good Fairy” (not the Lilac Fairy) with raised wand. In the background, a trail of rats precedes the Bad Fairy as she approaches on foot through an arch. The elaborate headdresses of the two fairies recall Paul Berain’s Furie Erinnis from his designs for the Sun King (fig. 11). Bakst placed the crown of the presumptive heir at the central axis of the painting, even though it is the smallest crown; the Good Fairy’s crown is the largest – larger even than the king’s crown, indicating the importance of magical power here. The presence of Aurora’s crown at the congruence of both vertical and horizontal planes signifies order and law as well as what is at stake in the tale, continuance of the royal line. The dominant arch in this scene sits at an angle to the rear plane of the picture. This echoes the scena per angolo utilized by Bakst in his backdrop for Scene I of The Sleeping Princess. However, it is important to note that Bakst had also used the scena per angolo in conjunction with the Christening scene in 1916, for Pavlova. This device of using the diagonal to disturb horizontal and vertical symmetries was developed by the Bibiena family during the baroque period and utilized in both architectural drawings and design of stage décor. Bakst’s reinterpretation of the Bibiena model will be discussed in detail below as it relates to the The Sleeping Beauty of Chaikovsky and Petipa. Yet Bakst’s adoption of the scena per angolo since at least 1916, and possibly earlier, in both the Rothschild panel and the first backdrop for Pavlova’s ballet, indicates that this was a significant element of his conception of the Christening scene. In the next panel in the sequence, the curse of the Bad Fairy (1922), the view is focused closer to the diagonal arch (which now reveals three inner arches hung with tapestries) (fig. 12). The pattern of the dark-bodied rats with tails extending to the left is echoed in the now-sinister depiction of the dark patterning on the nurse’s gown and its proximity to the dark spots on the robe of the Bad Fairy. Even the pattern of the tapestries resembles this visual motif. Here, Bakst used patterns not only for decorative quality (as was his wont), but also as a metaphorical representation of how the Bad Fairy’s evil has permeated the palace. Returning to Perrault’s original text, for the third panel Bakst depicted a Princess fascinated by an old woman spinning. The angle of the alcove in the high turret where the Princess spins is softened (fig. 13). The door is open as is the window that reveals the tranquil realm. The patterns on the floor, the dresses, and the hob-nailed wooden door with sun and moon are pleasing and varied; a bowl of milk awaits the cat playing on the floor. There are two portentous signs: the glare of the cat at an unseen object, and a silent, dark bird (perhaps a raven, but definitely not an eagle) that watches the Princess from the shadows of a lofty perch. This bird resembles the stuffed raven that Bakst kept on his study desk (fig. 14) in Paris, acquired in the 1890s after reading Edgar Allan Poe. In the undated final panel, the Prince kisses the Princess’s hand to break the enchantment (fig. 15). She wears her crown and, emphasizing that the lineage is intact, a large decorative crown adorns the top of her bed canopy. Again, Bakst’s fascination with decoration and ornament is in evidence: fleurs-de-lis adorn her coverlet and bed curtains, and form her crown; the carved stone arch over her bed contains stylized vines which are echoed in the vines covering her windows; the tile floor is an elaborate mosaic; and the carpet leading up to her bed depicts a phoenix, sign of rebirth. The variegated and exuberant patterns in stone and folds of tasseled drapery surround the simple innocence of the Princess with her flowing hair and plain nightdress. In this panel the view is direct and symmetrical. There are no diagonal angles as before. Bakst’s work on the Rothschild panels spanned several years before The Sleeping Princess and one year after the ballet, and thus has an important but tangential relationship to The Sleeping Princess décor. In the panels Bakst shows his mastery of narrative with regard to The Sleeping Beauty fairy tale and attention to focus and angles of view. 15 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bakst and Pavlova’s Sleeping Beauty (1916) Bakst’s first theatricaal encounter with The Sleeping Beauty came in 1916 when the ballerina Anna Pavlova commissioned him to design the sets and costumes for her abbreviated version of Chaikovsky’s ballet. [58] Bakst had worked intermittently with Pavlova in Russia as well as in the West. He designed her costumes for Chopiniana at the Mariinsky (1907 and second version 1908), The Dying Swan (1908) (fig. 16), Oriental Fantasy (1913, renamed Orientale for the American tour), and others. For the 1915-16 season the Anna Pavlova Ballet Russe company toured the United States and also appeared in a film called The Dumb Girl of Portici based on the opera La muette de Portici by Auber. Not wanting to return to Europe during wartime, and reluctant to repeat her own material while Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes (under the direction of Nijinsky) was in the U.S., Pavlova arranged with Charles Dillingham to produce The Sleeping Beauty at the New York Hippodrome. The ballet was part of a revue billed as The Big Show, the second year of Dillingham’s popular variety show. It opened August 31, 1916 and continued until January 1917. The Hippodrome was one of New York’s largest venues, with 5,697 seats. Its large stage, 160 feet long, could easily accommodate the first act “Mammoth Minstrels” (“400 – Count ‘em – 400,” according to the program), and in fact it was difficult to cast the large corps de ballet needed to fill out the stage for The Sleeping Beauty [59] (fig. 17). There were two performances a day, Monday through Saturday. Pavlova’s ballet was preceded by vaudeville acts, a circus procession of elephants that “played” a baseball game, and the aforementioned minstrel show. The Sleeping Beauty, called Act Two in the Hippodrome program, was followed by an ice ballet whose skater was billed as “The Pavlowa of the Ice,” a skeleton dance, and a suspended grand piano played by a man clutching the attached stool while a dancer, also suspended by a wire, turned on point on the piano lid (fig. 18). It was no wonder that the finale of Pavlova’s ballet included chorus girls dressed as fairies, attached to wires, rising above the stage. [60] The ballet was originally conceived in four tableaux that lasted about 50 minutes. A September 1916 review described Bakst’s scenography thus:

16 |

|

Fig.16 Fig.17 Fig.18 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Fig.19 Fig.20 Fig.21 |

|

The four tableaux as described do not match cleanly with the five illustrations in the programme (fig. 19). The first scene clearly takes place in the arched reception hall (top). The second tableau, showing the palace gardens, seems to take place in the second illustration. Ivan Clustine, Pavlova’s choreographer, had specified in his libretto that the Good Fairy would appear from behind the fountain, and there is a fountain at the center rear of this design. [62] The third illustration does not have a corollary in the description above. The fourth illustration of forest with castle in the background would seem to correspond to the Vision scene. Bakst could have intended the third illustration as a backdrop for the Hunt scene. However, notes from the R.H. Burnside Papers indicate that there was not a full-blown Hunt scene in the Pavlova production. Pavlova commissioned Bakst to design the sets and costumes at the end of June, 1916 and thus he had less than two months to complete the work. Because he was afraid to cross the Atlantic in wartime, Bakst sent his designs by post and did not oversee the execution of the décor. The reviews of Sleeping Beauty were not favorable, despite the acknowledged grace of Pavlova and enthusiasm for the colorful sets and costumes of Bakst. The New York Times, under the headlines “Dillingham Has Done It Again…but the Enchanting Pavlowa Is Hampered by a Badly Staged Ballet,” criticized the staging:

The “retold in song” remark alluded to recitatives sung by Letty Yorke, the Good Fairy, and Henry Taylor, the Bad Fairy. [64] After five weeks the ballet was reduced from fifty minutes to two scenes totaling twelve minutes.[65] The backdrops may have been changed at this time. Judging from two studio photos, at least one of the two backdrops was not Bakst’s design. In (fig. 20), the Christening scene, Aurora’s crib is in the center surrounded by the ensemble. Apart from the column pedestals with their embossed ovals, this design does not match the illustration in the Hippodrome programme. There is no extant sketch of Bakst’s that corresponds with the backdrop in this photograph, raising the possibility that a different backdrop was substituted. Another photo (fig. 21) of the garland dance shows the second backdrop with a fountain at its center rear. The design of this backdrop is not extant either, though the Hippodrome programme identified it as one of five illustrations belonging to Bakst. In any case, after three months a program of divertissements was substituted for The Sleeping Beauty. It is not known what backdrop(s) may have been used then. “Anna Pavlowa, premiŹre danseuse at the Hippodrome,” wrote the NY Telegraph,” made a complete change in her divertissement yesterday, and ‘The Sleeping Beauty’ is no more. It was replaced by a program of request numbers, selected from her repertoire. Slips were distributed throughout the audience last night announcing that Mme Pavlowa’s program will be changed at regular intervals, and a list of the artist’s favorite divertissements was submitted.” [66] Pavlova’s Sleeping Beauty was presented in a popular venue and on a stage too large for the ballet. For Bakst’s part, the artist never visited the Hippodrome and misjudged its dimensions. The scenic painter must have had difficulty translating a Bakst drawing of approximately 19 X 24 inches to a stage 160 feet in length. ) Bakst was accustomed to the much smaller stages of Europe; his later backdrops for The Sleeping Princess measured 46 feet in length.[67] These factors, coupled with the drastic shortening of the ballet, probably led to the excision of Bakst’s scenic designs. 17 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

A number of artifacts survive from Bakst’s work for the Pavlova Sleeping Beauty and shed some light on which designs were re-used or adapted later for The Sleeping Princess. These include set designs, costume designs, studio photos, and a number of actual costumes preserved at the Museum of the City of New York. Bakst’s design for Scene I, based on the Bibiena Atrio, was revised and used in 1921. (fig. 22) The hidden castle for Scene III, the Vision, was also revised and used in The Sleeping Princess. Two pencil studies for Scene V show the main attributes of Bakst’s final scene for The Sleeping Princess. (fig.23) and (fig. 24) Several paintings from 1916 were not used then but are extant: a forest scene (fig. 25) and a version of Aurora’s canopy bed hidden in the forest (fig. 26). Regarding Bakst’s costumes, three were planned originally for Pavlova in the role of Aurora. The first was entirely in gold, with what resembles a rose pinned at the bodice (photograph proofs, fig. 27). The second was for the Vision scene; Clustine had instructed Bakst that the “costume for the vision of the Princess should be fantastical, in the nature of a long shirt in some silver material falling below the knees.” [68] Bakst complied with a design annotated as follows for the costumier: (fig. 28)

There are no extant photos of Pavlova in this costume. Bakst’s wedding dress for Pavlova (fig. 29) included an elaborate wig and headdress, and heeled shoes. This dance was titled “Chaconne” in the Hippodrome programme and evidently was not danced on pointe. [70] Clustine suggested originally that the fairies’ costumes reflect their respective attributes; in the end he and Bakst made the costumes different colors, reminiscent of Bakst’s early work in St. Petersburg for Hedda Gabler. Schouvaloff reports that the usual number of seven Good Fairies was expanded to eight: “Beauty – Pink; Gracefulness – Lavender; Cleverness – Grey; Wisdom – Blue; Gentleness – Yellow; Goodness – Gold; Contentment – Rose: Happiness – White.” [71] The Bad Fairy was costumed in green. It is possible that the number of fairies was expanded to accommodate the dancers in Pavlova’s troupe (the ballet roles were filled from Pavlova’s troupe and the other dancers came from the ranks of chorus men and women). Bakst’s work for Pavlova in 1916 was generally of a high standard, yet poor execution of the production relegates his work to secondary consideration. His designs for the Christening, the Vision, and the Wedding in The Sleeping Princess have their roots in three of the set designs examined here. They testify to Bakst’s early interest in the Bibiena designs as models for the first and last scenes and his liking for the castle perched above a forest setting. 18 |

|

Fig.22 Fig.23 Fig.24 Fig.25 Fig.26 Fig.27 Fig.28 Fig.29 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Bakst and the Inception of The Sleeping Princess (1921) By the time a Ballets Russes production of the Chaikovsky/Petipa Sleeping Beauty was being contemplated in spring of 1921 (Stravinsky and Diaghilev were playing the two-hand score while in Seville for Easter Week), Diaghilev and Bakst had not collaborated on a ballet, and likely had not spoken, for some years. Bakst’s last realized production for Diaghilev was Les Femmes de Bonne Humeur of 1917, on which Bakst was working in Rome when he wrote to Wormser about the Rothschild panels. At that time Diaghilev had spoken with Bakst about plans for La Boutique Fantasque to be choreographed by Léonide Massine. Bakst was enthusiastic and soon produced a number of designs. Because of the war, Diaghilev was not in a position to stage any new ballets in 1918, although he did commission new scenery and costumes from Robert and Sonia Delaunay for CléopČtre. The troupe toured Spain in the spring of 1918 and finished in Barcelona, broke and without prospects. A number of dancers departed. Through the intercession of Sir Oswald Stoll, owner of the Coliseum and the Alhambra Theatre, and various diplomats, permission was secured for passage of the troupe through France to London in the summer of 1918. Stoll wired Diaghilev £1,000 to transport such dancers, sets, and costumes as remained. Diaghilev cobbled together a season at the Coliseum of older ballets and more recent ones unfamiliar to British audiences. [72] Most of the backdrops were repainted by the Russian émigrés Vladimir and Elizabeth Polunin, whom Diaghilev met for the first time in London.[73] A shift had occurred after the war in Diaghilev’s views toward Ballets Russes décors. In spring of 1919 Diaghilev revived the idea of La Boutique Fantasque but no longer wanted Bakst’s input; he had decided to ask André Derain to create the décor. By precipitously demanding the completed designs of Bakst, Diaghilev engineered the rescission, which Bakst took badly. Coinciding with the development of Massine, as his in-house choreographer, was Diaghilev’s shift away from the Russian artists such as Bakst, Benois, Boris Anisfeld, and Mstislav Doboujinsky at this time. For the new ballets of 1919 Diaghilev engaged easel painters active in Paris, including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Derain.[74] According to Massine, Diaghilev desired a “change from lavish splendour to simplicity and rigid artistic control.” [75] Polunin wrote, “Having dealt so long with Bakst’s complicated and ostentatious scenery, the austere simplicity of Picasso’s drawing [for Le Tricorne, 1919], with its total absence of unnecessary detail, the composition and unity of the colouring – in short, the synthetical character of the whole – was astounding. It was just as if one had spent a long time in a hot room and then passed into fresh air.”[76] What Diaghilev wrote in the program for La Boutique Fantasque was perhaps the most telling of the shift away from Bakst’s style of décor:

19 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

Diaghilev managed deftly to praise Bakst and the other artists, who had a large and undeniable part in the establishment of the Ballets Russes, while at the same time criticizing their painting as “careless.” Diaghilev attached the descriptor “decorative artist” as a pejorative to Bakst and the rest and classified their work as pastiche and passé in order to promote the newer artist. It is significant that Diaghilev described Derain as “a renovator of the purest French classical painting”; Diaghilev’s comment pointed to a larger aesthetic debate taking place in France and, to a lesser extent, in England. Several London critics echoed this view of Derain’s décor for La Boutique Fantasque. For example, Clive Bell wrote in the New Republic, “M. Derain, besides being one of the best, is one of the gravest and most scholarly of modern painters. Only a simpleton could suppose that because he uses the new post-impressionist idiom he is not perfectly classical. He has the traditional French taste for a severe palette – black and white, grays, greens, and browns. His harmonies are discreet and distinguished. His design simple.” [78] This same “severe French palette” had previously been perceived as nondescript compared with Bakst’s 1909-10 décors: “No Frenchman,” wrote Martin Birnbaum in 1913, “nor any artist influenced by French ideas, would have dared to use such a gamut of brilliant colors at a time when our drab, occidental culture sought appropriate expression in flat subdued tones.” [79] By 1919, austerity and restraint, including a limited palette, were valued over exuberance. Roger Fry expressed this sentiment in Current Opinion,

20 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

Fig.30 Fig.31 |

|

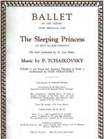

And it was not only the English who extolled such “virtues of economy”: Maurice Brillant wrote in Le correspondent that the new French artists demonstrated a “great care of construction, a great austerity, and a sobriety provoked by renunciation of impressionist colors.” [81] With The Sleeping Princess, Diaghilev and Stravinsky were intent on preparing the ground for acceptance of Chaikovsky’s music, particularly in France, within the context of revived interest in French “classical” music composers such as Rameau and Charpentier. That The Sleeping Princess did not survive to open in France was yet another bitter aspect to the production’s failure. Yet clearly, from the vantage point of 1921, Bakst’s style of décor represented an aesthetic that Diaghilev had shunned for several years. By the

summer of 1921 plans to stage The Sleeping

Princess had moved forward and a designer had to be chosen. Through Sir

Oswald Stoll, Diaghilev had secured the use of a London venue for six months

(beginning in October of that year) and a substantial advance of £10,000

toward the new production. The venue was the Alhambra Theatre on Leicester

Square, seating 1,800, and the Alhambra Company was the benefactor. [82]

Diaghilev asked his long-time friend Walter Nouvel, then his business

manager, to approach Benois, who was a natural candidate to produce the décor

given his special interest in the court of Versailles. However, on July 8,

1921 Nouvel telegrammed Diaghilev that Benois was unable to circumvent his

responsibilities as curator of the Hermitage Museum and could not leave

Russia at that time. [83]

Bakst in Paris was thus quickly recruited as a second choice. By July 16

Bakst had joined Diaghilev, his new secretary Boris Kochno, and associate

Randolfo Barrochi for discussions in England. [84]

Knowing that Diaghilev was already under tremendous time pressure to produce

a ballet in three months, Bakst negotiated a demanding agreement. His terms

were: a fee of Frs. 28,000 (five scenes at Frs. 5,000 each and Frs. 3,000 for

“expenses”); the inclusion of the words “The entire production by M. Léon

Bakst” on the program, just below the title (and above the names of

Chaikovsky, Stravinsky, Petipa, and the régisseur

Nikolai Sergeyev); and the promise of a commission to design the upcoming Mavra. These terms were not honored.

“The entire production by M. Léon Bakst” did appear on The Sleeping Princess

program, but in substantially reduced type (fig. 30) and (fig. 31). Bakst

was never paid for his Sleeping

Princess décor. Probably most of Stoll’s advances went to purchase cloth

and trim for the backdrops and costumes, and to pay the costume-makers and

scene-painters, who would not have delivered them otherwise. As an added

insult, the Mavra commission was

given to Léopold Survage after Bakst had begun work on it. Several

biographers of Bakst have incorrectly stated that Bakst had only six weeks to

produce the enormous quantity of sets and costumes. Bakst in fact had over

three months to work on The Sleeping

Princess, from the July 21 meeting until the intended premiere date of

October 31 (which was pushed back to November 2, probably due to the

last-minute change to the Awakening set). Levinson, long a champion of Bakst,

glorified Bakst’s efforts as nothing short of heroic: “In less than six weeks

– his time was necessarily restricted – Léon Bakst composed, or, rather,

improvised the six scenes and the three hundred costumes (a whole world of

pictorial fiction) which the ballet contains. A less bold, more timorous

worker [Benois?], seeking the exact historical document, nosing about in

portfolios, compiling dossiers, would have succumbed to the difficulties.

Bakst, above all else an imaginative artist, triumphed. Instead of building

up an imitation, he created a dream of reality.” [85]

It is possible that Spencer was repeating Levinson’s error when he asserted that “Bakst had six weeks to mount this most demanding of ballets.” Spencer added his own conclusion, “He was already a sick man,” as a mitigating factor for the failure of The Sleeping Princess. [86] As it was, three months was a tight schedule to meet from a décor standpoint, as it was also in securing the necessary numbers of dancers trained in the Russian classical style and rehearsing all the ensemble numbers. Yet, however intense the time pressure was for The Sleeping Princess (and probably most Ballets Russes premieres were similarly pressured), it is inaccurate to suggest that Bakst’s designs were either precipitously conceived, or mostly derivative. Bakst’s remarks to Diaghilev in 1919, about La Boutique Fantasque, could be applied equally to The Sleeping Princess: “The whole secret of the success of the way I design productions is that I take to heart every one of them and finish off the work of the choreographer or author of the ballet…. As usual, I have imagined everything on a grand scale.” [87] 21 |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

The Sleeping Princess was an extravagant spectacle, like The Sleeping Beauty before it. Once the contract was signed, Diaghilev and Bakst (and Stravinsky and everyone else) did not hesitate to achieve the most lavish production possible. For the Russian émigrés, The Sleeping Beauty was synonymous with splendor, spectacle, and excess. Diaghilev and Bakst probably attended a Mariinsky revival of the 1890 production in 1903 with original décor. There was a second production in 1914 with new décor by Korovin, necessitated by the poor state of the original costumes. [88] At the time of its premiere balletomanes and critics in St. Petersburg faulted Director Vsevolozhsky’s costumes as overwhelming the choreography with decorative elements. The following appeared in the Novosti i birzhevaya gazeta the day after opening night, “Silk, velvet, plush, gold and silver embroidery, marvelous brocade materials, furs, plumes, and flowers, knightly armour and metal decorations – it is lavish, and the richness is showered on the adornment even of the least important characters.” [89] The reviewer could have been describing Bakst’s costumes of thirty years later. The level of decorative detail specified in his drawings of 1921 was extraordinary, down to the elaborate costumes for the pages and guards (fig. 32). Another St. Petersburg critic addressed the line crossed (he wrote) from tasteful sumptuousness to carnival excess in The Sleeping Beauty:

The Mariinsky production consumed more than a quarter of the production department’s annual budget of the Imperial Theatres for the 1890-91 season. [91] Like its predecessor, The Sleeping Princess production was mounted at tremendous cost. Under financial pressure from his directors and without hope of recouping his investment, Stoll announced that the ballet would close on February 4, 1922. Diaghilev borrowed money from the mother of one of his English dancers and left London in some haste, before the final performance. As he feared, the sets and costumes were seized against the monies owed the Alhambra, reportedly £11,000.[92] Thus Diaghilev could not fulfill his contract with Jacques Rouché of the Paris Opéra for a spring engagement of The Sleeping Princess. Many of the dancers were not paid and scattered to look for work elsewhere. Olga Spessivtseva, one of the Auroras, returned to the Mariinsky and danced in Fedor Lopukhov’s revision of The Sleeping Beauty (October 1922). [93] Bakst, citing his non-payment, filed a lawsuit in 1923 that banned Diaghilev from using the sets and costumes he designed. Meanwhile, the décor materials were lying in storage underneath the Coliseum stage and unavailable. MacDonald reports that “Some years later, a tank used for a diving act leaked, and rumour had it that they had all been ruined. This was turned into a diatribe against Stoll, who was accused of rank carelessness in their storage.” [94] In fact, many of the costumes, and the backdrop of one of the scenes, did survive. [95] Stoll wrote to Diaghilev on September 23, 1924, that “it is hereby confirmed that no proceedings will be taken against you for the recovery of your debt to the Alhambra Company Limited, and on settlement in full of the said sum of £2,000, the whole of the production of “The Sleeping Princess” will become your property.” [96] In the letter, Stoll allowed Diaghilev to pay him £30 per week for a seven-week engagement at the Coliseum in fall of 1924. It may be inferred that Diaghilev remitted the remaining £1,790 and repossessed the sets and costumes, since The Sleeping Princess sets and costumes, in addition to materials from other ballets, were in storage in a warehouse outside Paris at the time of Diaghilev’s death in August 1929. However, he never again used The Sleeping Princess sets and costumes. (It is assumed that Diaghilev was released from Bakst’s injunction due to the latter’s death in December of 1924.) The dancer and choreographer Leonid Massine managed to obtain legal control of the properties, after Diaghilev’s death, with the intention of using them for a troupe assembled to perform in New York. This venture fell through after the U.S. stock market crash, when backing was withdrawn from the Broadway producer E. Ray Goetz. “My contract was cancelled,” wrote Massine, “and I found myself the owner of all the Diaghilev material, stored far away in Paris, with no means of using it.” [97] Various sets and costumes of the Ballets Russes, including the Scene V backdrop from The Sleeping Princess, came to be used by the company of Col. de Basil. These materials were not, however, owned by the de Basil company; they had been purchased from Massine in 1934 by a foundation backed by the London Committee of Friends of the Ballet. When de Basil died in 1951, the company disbanded and the costumes and scenery were again warehoused. According to Anthony Diamantidi, member of the controlling foundation, the annual storage cost of £10,000 became too onerous and the materials were finally offered up for auction in 1967.[98] Richard Buckle, engaged by Sotheby’s to investigate the materials and their potential for auction, describes how these relics came to light: 22 |

|

Fig.32 |

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

Many of the Diaghilev ballet

materials were present in this collection. The portions from The Sleeping Princess included about

160 costumes or parts of costumes (cloaks, trains, skirts, or jackets) and

the backdrop and two side legs and pelmet from Scene V. These items were

auctioned by Sotheby’s on July 17-18, 1968. Bakst’s Scenography and Costumes for The Sleeping Princess By the time of The Sleeping Princess Bakst’s aesthetic sensibility in terms of theatrical design had been developing for nearly twenty years, yet his experience designing for large-scale ballets was scant. As discussed above, Bakst’s involvement in Pavlova’s 1916 Beauty was at arm’s length, and was very different from the close collaboration among principals that occurred in the 1921 Diaghilev production. For Diaghilev, Bakst had nearly always operated within the framework of the characteristic Ballets Russes one-act ballet. This was not always the case for his work outside the Ballets Russes, some of which was not for ballet. [100] Bakst attained his command of color and mood, what he termed “tone,” in a short format in which all aspects of the ballet were brought together in startling combination and sustained for about thirty minutes. One could argue, and scholars do, about whether that kind of synthesis was achieved in each of the new ballets produced under Diaghilev’s aegis. But it is never in doubt that some kind of concordance, or even deliberate discordance, was a Ballets Russes goal in combining the elements décor, dance, and music. For The Sleeping Princess, this goal of aesthetic fusion had to be approached differently from ballets created from the ground up. As a revival with existing music and choreography, each of the principals had their own task: Stravinsky was to update, orchestrate, and interpolate sections of the score; Nijinska was to compose some new dances and to re-create and sharpen some of Petipa’s choreography. Whether or not Diaghilev had explicitly imagined this, Bakst took upon himself the task of unifying the whole. His resulting décor was a response to the question of how to capture in image, to create one sweeping impression of, a large and complex work comprised of five very different scenes, spanning more than a century. Bakst’s response was to create a narrative arc through a progression of scenic designs, each stationary yet when experienced in sequence creating a large-scale kind of rhythm. Within this larger framework, Bakst designed the dancers’ costumes with regard to their individual character, as well as their effect en masse – a kind of choreography in its own right. Shunning slavish adherence to historical detail in the costumes, Bakst strove to complement each scene’s décor with the colors and textures that would most enhance the backdrops. To each scene was bestowed a different mood and Bakst reflected this in his costumes: the sparkle of the fairies and richness of the court, the garlands and villagers in a rustic garden scene, dusky autumn colors against a dark forest, misty nymphs and visions, and the gaiety of a wedding celebration replete with fantastical fairy tale figures. [101] In the five scenes for The Sleeping Princess the artist manipulated color and line, changes of scale, perspective, and other theatrical devices to shift mood and focus. Some of The Sleeping Princess backdrops were broad and expansive, open to the sky or suggestive of unexplored rooms and hallways; others were intimate, moody, veiled. For the public scenes that frame The Sleeping Princess – the palace in Scene I where the baby Aurora is christened, and the Scene V setting for the series of divertissements celebrating the betrothal of Aurora and Prince Charming – Bakst drew his inspiration from the Bibiena’s seventeenth century set designs for operas, and from Charles de Wailly’s eighteenth century design for Gluck’s opera Armide. In these two designs Bakst combined retrospectivism (that is, reference to past stage designs) with an architectural use of line and perspective to literally delineate the stage space and render the scenic backdrops appropriate for public rituals. Further, Bakst’s strong visual lines reinforced the ideas in the libretto regarding social hierarchies sustained by order, balance, rules, and clear-cut demarcations. Scene II, the Spell, was in scenic terms a transition with strong directional lines of a colonnade and landscaped garden balanced by shadowy trees and shrubbery. This scenery foreshadowed the forest encroaching on the royal castle for the hundred years’ sleep. In the inner scenes of The Sleeping Princess, Scenes III and IV, Bakst created a twilight world where visions and inner yearnings were veiled by scrims, expressed in saturated colors, and a rose-red bedroom softened by moonlight where the sleeping princess lay amid an over-sized canopied bed, protected by an enormous black eagle. 23 |

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

|

|

|

The